Have you ever given up on learning a new skill? Maybe a new language or a musical instrument? I can’t count the number of hobbies I have given up on, from sport to martial arts, drawing, piano, the list goes on.Why did you give up? Did you feel you were not progressing fast enough?

Walking is an extremely hard skill to learn. Toddlers between 12 AND19 months practice more than 2000 steps per day and fall on average 17 times per hour. That’s about 100 falls per day and 3000 falls per month.

That’s an insane failing rate, but we don’t give up. We work it through.

But as we grow older, that incredible resilience wears away, and we become discouraged more easily.

Have you ever given up on learning a new skill? Maybe a new language or a musical instrument? I can’t count the number of hobbies I have given up on, from sport to martial arts, drawing, piano, the list goes on.

Why did you give up? Did you feel you were not progressing fast enough? That maybe you didn’t have any talent for it, or it wasn’t meant for you? Or you lost all your will after watching kids on YouTube shredding their guitars? (Note to self.)

Discovering a new hobby you’re passionate about and want to master doesn’t happen every day. I’m sure you remember how excited you felt when you encountered it. And that excitement and passion probably stayed around. For a little while, anyway.

But then you lost interest or found something else more exciting, and before you knew it, that little new hobby had been added to a long list of abandoned endeavors.

Welcome to the Valley of Disappointment. You’re not alone

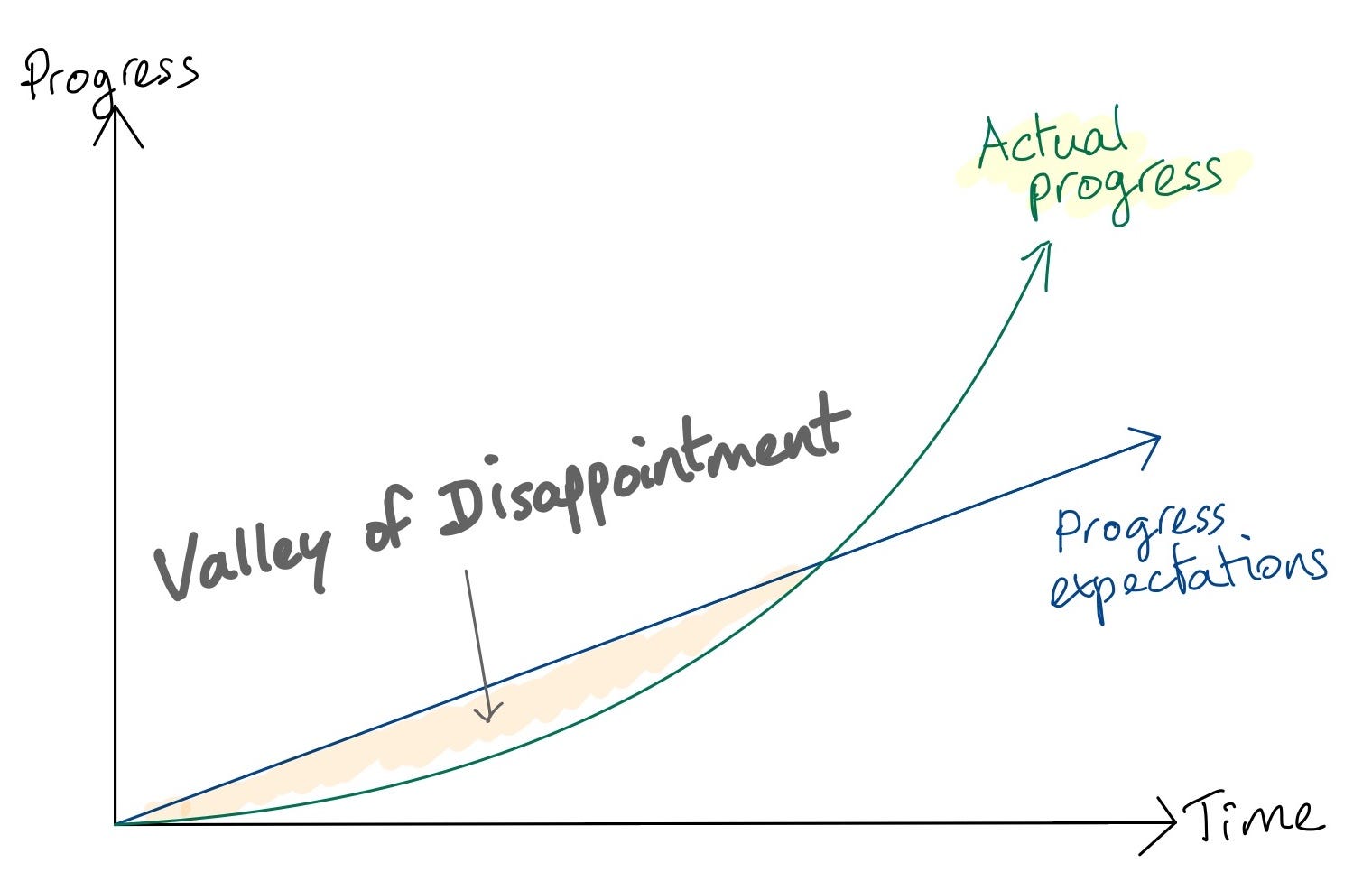

“Valley of Disappointment” is a concept introduced by James Clear in his book Atomic Habits, which I previously referred to in my article about frictionless note-taking.

The idea is that progress usually doesn’t happen linearly but more exponentially. We get a fraction better at what we are doing over a certain period, with progress compounding over time. For example, if we were to get 1% better at playing the piano every week, that would be equal to multiplying our capability (whatever that quantifiably means) by 1.01. From there, 2 weeks would then be 1.01 * 1.01, a year would be (1.01)^52 = 1.68, two years would be (1.01)^104=2.8, etc.

I see the math guys coming for my head: “But if you start at zero, then 1% of zero is still zero!”. I know. Leave me alone. You get the point!

Exponential growth means that the longer we practice, the greater we progress, each week progressing a little more than the previous week.

Our problem, though, is that our expectations are linear. We expect steady progress from day one, which creates a gap between our actual progress and our expectations. That gap is what James calls the Valley of Disappointment, or “plateau of latent potential”.

The important part here is that eventually, the exponential curve will cross over the line of our expectations. But the time where the exponential curve is below the line is when we are most likely to give up on practicing something because our progress won’t match our expectations. Thus, the Valley of “Disappointment”.

If only we could keep practicing long enough to get over the line, most of us probably wouldn’t give up on our passions or hobbies, and we would feel more accomplished as a result.

Is there anything we can do to maximize our chances of escaping the Valley of disappointment?

Keeping our expectations in check

That’s probably going to sound very obvious, but the reason that the Valley exists in the first place is because of our inflated expectations. Lowering our expectations of progress is the first piece of the puzzle.

Why are our expectations so high to begin with?

Fallacy of linearity

As a survival mechanism, we have an innate capability of seeing straight lines between two points; that allows us to go from point A to point B using the minimum amount of calories necessary. We also seem to understand quantities and equivalence naturally. If one fish buys me two apples, I expect two fish to buy me four apples.

For the same reason, we naturally expect the same amount of effort to reward us with the same progress level.

We need to recognize that we are simply being victims of a linearity bias and accept that progress will be small and most likely inconsistent for a little while.

Misplaced comparisons

We are social animals (yes, you too), and we can’t help but compare ourselves with others.

While it can be helpful to gauge our progress in absolute terms, it is usually not very healthy (and probably not very encouraging) to compare ourselves with our peers and set expectations accordingly. I see three main reasons for that:

- They may be naturally more talented or have some unfair advantage (like being the child of a piano teacher)

- They may be practicing way more than they admit

- Maybe they are failing at everything we can do, but that’s the one thing they have success with

In short, comparing ourselves to others puts us at risk of being victims of the Survivorship bias, where we only see the successful few and not the unsuccessful many.

Impostor syndrome

The more we know about something, the more we feel that we’re just scratching the surface. There is a neat analogy that I wrongly attribute to Neil deGrasse Tyson, which says that knowledge is like an expanding sphere, with its surface being the frontier between the known and the unknown. The bigger the sphere becomes, the larger its surface increases.

(Could that explain why ignorant people believe they know everything?)

This ever-increasing surface of the unknown can be overwhelming and make us believe that we know nothing, that we are “impostors” in our field. This syndrome can be extremely demotivating, especially if combined with a comparison with others.

Now that we have a good understanding of what is skewing our expectations, let’s look at how we can maximize progress.

Flow is the word

We’ve all heard about “flow” – this state of extreme focus when productivity goes through the roof. We feel “in the zone”, able to absorb anything we learn, like a dried sponge in a bucket of water.

To get the most bang (progress) for our bucks (efforts), we should aim at reaching a state of flow whenever possible. According to Friederike Fabritius and Hans W. Hagemann in The Leading Brain, there seems to be a recipe for it:

To achieve flow, you need a well-defined goal, an optimal challenge, and clear, immediate feedback. The goal supplies acetylcholine to help maintain your focus, the challenge triggers noradrenaline, and the feedback provides you with a rewarding burst of dopamine.

Optimal challenge

Having well-defined goals is a critical first step. We obviously want to set for ourselves goals that are achievable, otherwise, we won’t feel that we are progressing.

But at the same time, we need these goals to be somewhat challenging. Being slightly outside our comfort zone will release noradrenaline.

Noradrenaline is at an optimal level when you feel slightly overchallenged; it leads to a “this is tricky but I think I can handle it” feeling. It is also released when you push yourself to perform a difficult task better, faster, or with fewer resources.

Of course, optimal levels of challenge seem to vary from person to person.

There is no standard for optimal arousal

Some people can become quickly overwhelmed and anxious. In contrast, others need to have Mission Impossible’s BGM in the back of their head to get anything done (I’m unfortunately more of the latter).

Fabritius and Hagemann mention that there seems to be a correlation between the intensity of arousal needed and levels of testosterone, which can widely vary between genders and with age. People with higher testosterone levels will require more intense arousal; alternatively, they will also be less prone to anxiety and stress (they probably die younger too.)

As we’re all different, we’ll need to find the right amount of challenge for us. It may sound a bit laborious, but trial and error is probably the way to get a sense of that amount.

Now that we’ve covered noradrenaline let’s talk about the “Kim Kardashian” of hormones; dopamine.

My name is Guillaume, and I’m a dopamine addict

Dopamine is probably the most famous hormone or at least the most popular in productivity literature. It is also the most addictive. And there’s a good reason for that. Dopamine rewards us for all the efforts we make that are necessary for our survival, from finding food to learning new skills.

It also helps us focus on what needs to be done.

Dopamine is involved in your ability to update information in memory and also affects your ability to focus on the task at hand.

Every time we learn something or acquire a new skill, a neural pathway gets created, and dopamine is released as a reward. The amount of dopamine released depends on many factors, but one of them is novelty; we are incentivized to acquire new information and skills to increase our adaptability and improve our chances of survival.

Its effects are strongest when the stimulus that generates it is new. This explains in part the enthusiasm you may feel when you start a new project and why the thrill isn’t usually as strong after you’ve been working on it for a while.

Adding some form of novelty into any practice can help strengthen the action/reward feedback loop and keep us motivated and willing to learn more.

This being said, dopamine is a hormone focusing on short-term rewards; long-term goals won’t stimulate it. If our goal is to learn the piano, we need to breakdown that long-term goal into smaller achievable goals, like learning songs or practicing scales and make these goals progressively more challenging. That is our best chance to reach a state of flow.

Routine at the rescue

As a foreign language learner myself, I know how challenging and overwhelming an endeavor it is. I’ve been learning and practicing Japanese for close to 20 years now, and while it’s not something I spend conscious effort on anymore, there was a time when I would practice rigorously every day.

Now, “improving my Japanese” is not a measurable goal and not really achievable in the short-term. But practicing 30 minutes of vocabulary is.

For example, learning 10 new words per day is a good goal. It is easily trackable, slightly challenging; it involves novelty (new words!) and doesn’t require too much time to complete.

The perception that a goal is achievable within a reasonable amount of time is key. It will facilitate the production of dopamine, thus increasing our motivation and focus. It may even allow us to reach a state of flow.

Note: For those interested, I’m planning a future article about how I learned Japanese, or possibly even a series, so keep an eye out for that.

Now, did you get better by just learning 10 new words? Only slightly, yes. But over a month, that amounts to 300 words, and more than 3000 after a year.

Eventually, the number of words you can learn per day will increase. If not the number, the complexity of the words will.

That’s the power of a routine. Small steps add up to long distances over time.

When it comes to routines, I strongly recommend reading Atomic Habits, as mentioned earlier. I also introduce the concept of routine building in my article on note-taking (second shameless plug).

Trust the system

But remember our goal: avoid getting lost in the Valley of Disappointment.

Learning 10 words per day will not make you fluent. At least not in the beginning. Even after a few weeks, you’ll still feel that you’re not making much progress. The words you’ve learned do pop up in conversations from time to time, but you’re still not understanding 90% of what’s being discussed.

But eventually, as time goes, you’ll start understanding more and more, and it will become second nature. You need to trust the system. Don’t let you get discouraged by your unreasonable expectations.

When I was learning new vocabulary very actively, I would tell myself that the words I’m learning today will be mine in six months. I’m investing in my future self, and it will thank me for it.

I wasn’t expecting immediate returns because I knew that, eventually, I would rip these returns. I’m convinced that this mindset is what allowed me to keep learning, especially during plateaus.

The bright side

80% of people who started a Gym membership in January will be gone by May. They all probably had different motivations for starting their membership, but they all have one thing in common: they all gave up.

For the sake of this article, I’d like to think they got lost in the Valley of Disappointment. It’s hard to stick to a routine when our expectations don’t match what we can realistically accomplish.

Although I don’t have any statistics to back my claim, I’m convinced that we give up on 80% of our new endeavors. And that’s really sad.

But the flip side of this coin is much brighter. If you don’t give up, you’ll do better than the 80% who did. Perseverance sets you 80% ahead of the curve.

The great escape

Any time we start a new endeavor, sooner or later, we’ll walk into the Valley of Disappointment, and once we get lost in it, there is no easy way out.

So, here is my escape plan.

- Decide how important this new endeavor is and how much time per week you are willing to invest in its practice.

- Reflect on your expectations: Are you comparing yourself to others? How badly do you want to see results quickly? Acknowledge that the higher your expectations, the deeper the Valley will be.

- Break down your practice into small, slightly challenging, but achievable goals, and create a routine of achieving them consistently; it is your best chance to reach a state of flow.

- Remind yourself that you need to trust the system. You’re investing in your future, and your future self will thank you for it.

- Remember that perseverance is the only difference between the quitters and the achievers. Which one are you?

Oh, and don’t forget to have fun in the process! That’s what learning should be. Fun.

What I’ve learned

- Getting good at anything takes time and perseverance.

- It is hard to persevere when we can’t see progress.

- Our expectation of progress is what demotivates us, not the absence of progress.

- We are all different and shouldn’t compare our progress to others.

- We each have our own “zone”, and there is no “one size fits all” recipe for reaching a state of flow. We need to find by trial and error the right amount of challenge that works for us.

- Setting a routine and trusting the system will evolve into perseverance.

- Not quitting sets us ahead of the curve.

I know that life is not a competition, but acquiring new skills can open doors for new possibilities. It can also help giving depth and maybe even meaning to our lives.

Ultimately, we are what we learn.

References

- The Leading Brain, Friederike Fabritius, Hans W. Hagemann

- Atomic Habits, James Clear

- The benefits of frictionless note-taking, yours truly