Procrastination is the thief of time —

I’m a curious and optimistic person, and I’m always on the lookup for new tools that would magically solve my clinical tendency for procrastination, which I prefer calling “unassumed perfectionism.”

A few months ago, I was randomly watching videos recommended by Youtube’s algorithm (as any creative mind does I assume), and I stumbled upon a video entitled “How I Organize My Life with Roam” from a Youtuber named Ali Abdaal. Ali has many videos on productivity on his channel, and Roam is what he calls a “glorified” note-taking app.

I strongly recommend watching the video, as I won’t do it any justice by summarizing it here, but suffice to say, I was immediately sold on the idea of tracking every element of my life in one tool and drawn to the simplicity of the user interface. I signed up for the one month trial and started using it right away.

I have been using Roam every day since, and while it hasn’t solved my unassumed perfectionism yet (bummer), it has had a profound impact on my creative process and how I record my thoughts and ideas, and how I consume them. My goal with this piece is not to offer a review of Roam — there are plenty out there — nor to try to convince you to use it. I want to share my self-reflection on why it had such a profound impact on me.

What are the benefits of taking notes?

Quick disclaimer: I have no expertise on the subjects I’m talking about, so please view this as my non-expert, non-authoritative opinion on the matter, although I do hope you’ll be able to relate to my thoughts and reflections.

Before I get into Roam's nuts and bolts and how it impacted me, I thought it might be useful to reflect on the benefits of taking notes in the first place.

Aside from keeping us awake at school or during boring weekly meetings, I believe that taking notes, either physically or digitally, can help us with the following:

Visualizing thoughts and ideas: Putting on paper (figuratively speaking) can literally help us visualize an idea with words or shapes, rather than a fuzzy, sometimes incoherent concept in our head.

Enhancing our thinking process: Although we may feel otherwise, our brains are not good at conceptualizing complex ideas. Writing down our thoughts allows us not to juggle in our head with several concepts at once and focus on what our brains do exceedingly well: finding patterns and connections between the words we wrote down.

Memorizing: Taking notes, in particular on paper, helps with memorization, and we all have sweet memories of wrist pain as a result of frantically writing over and over the same stuff on a piece of paper before an exam until it makes its way to our mid-term memory (or it doesn’t and we succumb to the pain)

Putting words to feelings and emotions: Our brains are incredibly efficient and ridiculously flawed at the same time. Somehow, the part of our brain that controls our emotions, the Limbic system, hasn’t been equipped with language capabilities. While emotions dictate the vast majority of our decisions and actions in life, we, however, can’t explain them with words (I’ve just given you the perfect excuse for when your significant other complains that you never say how you feel. You’re welcome). Self-reflection, journal writing, and other similar practices attempt to put words to these emotions by writing them down.

Unloading our brain: A personal favorite of mine. We have busy lives with many decisions and things to think about, some more important than others. This constant activity overloads our brain, which will thank us with a generous dose of anxiety and stress. Writing down ideas, thoughts, things we don’t want to forget, things we are concerned about, etc., can allow us to unload the poor fellow, facilitate focus, and ultimately lower anxiety and stress levels.

Making us smarter: Assuming we review our notes, the obvious upside of taking notes is that it allows us to build our personal knowledge base over time, helping us making (hopefully) more informed decisions.

I would love to discuss note-taking techniques, but I think it is outside of this piece’s scope, and I’m sure it would be a fascinating topic for a future article.

Why do we end up not taking notes? It’s not entirely our fault

With all the benefits mentioned above, how come many of us don’t take notes, or only sporadically? In my view, there are two main reasons.

We never learned how to take notes efficiently

Do you remember learning at school how to take notes? The only thing I remember was writing the fastest I could to catch as many words as possible from what the teacher was saying.

Do you remember learning at work how to take notes during a meeting? I just remember being told by my boss always to bring a notepad and a pen to a meeting so I could take notes, because … you never know!

Reflecting on how beneficial note-taking is, I’m actually baffled that note-taking techniques are not taught as part of compulsory education while calculus is (and don’t get me wrong, I was a math major, and I loved calculus).

We fail at building a habit of consistently taking notes

Assuming we understand the benefits of taking notes, what is stopping us from making it a habit?

James Clear, in his book “Atomic Habits,” explains that any habit, good or bad, is a feedback loop composed of four elements: cue, craving, response, and reward. “cue” is the trigger, “craving” is the appeal, “response” is the actual action we perform in response to the craving, and “reward” the end goal of the habit, what we craved for. Grossly simplifying, a habit is simply a pattern registered in our brain that recognizes a cue, associates it with a craving, and triggers a response to get a reward. For example:

- cue: I see a notification on Whatsapp

- craving: I want to know who contacted me and what for

- response: I open the app and read the message

- reward: my curiosity is satisfied, and I feel more connected (both dopamine and oxytocin are released)

My brain associates “notification on Whatsapp” with “feeling good.” If this pattern is recognized repeatedly, a powerful habit will be created (most likely unwillingly in this case).

Following the previous example, a note-taking habit could look like this:

- cue: I have an idea or thought

- craving: I want to write it down not to lose it because it might be useful in the future. It will reduce my anxiety too

- response: I write down the idea or thought

- reward: I feel good about it. I feel relieved of the burden of that thought and happy that I invested in my future

What if we actually wanted to create that habit? James proposes a framework to maximize our chances of success that he calls “the four laws of behavior change”: make it obvious, make it attractive, make it easy, make it satisfying.

We can see how the notification example fits the bill:

- Notifications are designed to be as obvious as possible.

- Satisfying our curiosity and feeling connected is very attractive.

- Opening the app and reading the message could hardly be made easier.

- The reward is, indeed, quite satisfying.

With such a level of fulfillment of the four laws of behavior change, no wonder we end up addicted to messaging apps.

Conversely, missing one or more of these laws would logically make it harder to form a new habit, even if we wanted it badly.

Let’s apply this logic to our note-taking habit example. The cue is relatively obvious, and the craving’s intensity will depend on how attractive the reward is, so our main concerns should be the response and the reward. And case in point, that is where we fall short.

First, the reward. I see two types of reward: a short-term reward, the relief of writing down the thought to free up our mind, and a long-term reward that corresponds to our investment’s future dividends.

While we can expect the short-term reward, the long-term reward won’t be felt immediately, as it will take time before we see the actual dividends of our past investments. Until we get to that point, we need to accept that our craving will be half as intense as we would like it to, at least for a little while.

And that brings us to the most crucial part in my view, the response. “Make it easy,” James says. Here, we are talking about ease to act, or in other words, low friction. If friction is too great, it will counteract the momentum of our already not so intense craving, and the reward won’t be enough for us to complete the action, failing to reinforce the feedback loop in the process.

Reducing friction is the key to our salvation

Friction kills ideas

As human beings, we all share something in common. We hate making decisions. It’s a stressful and tiresome process involving cognitive and emotional activity, and very often, we would rather put up with an uncomfortable situation than deciding to change it. I like to think that we wake up with a daily decision budget and that every decision we make consumes our budget until it gets depleted, and we lose the will power necessary to make any more decisions.

There is a famous principle in product design called “Don’t make me think.” It is a cornerstone of usability, and it means that products should be intuitive, that I shouldn’t need to have to think about how to use a product before using it. I personally think it should be renamed to “Don’t make me decide”; let me use this product without asking me to make any decisions before.

When responding to a craving, every decision needed until the action's completion will be additional friction. It is like having your notepad upstairs, and every decision is an extra set of stairs to climb.

What sort of decision am I talking about?

For analog note-taking, it could be:

- Which notepad to use?

- Should this be on a new page? How should I name the page?

- I had a similar idea a few days ago. Should I put this one next to it with a date? Where did I put that idea last time again? I can’t find the page …

- Is this idea really worth all the trouble?

For digital note-taking (which is more my thing), it may look like:

- Where should I put the note? Should I create a new document on Google Docs? How to name it?

- Is it the right folder for this document? I probably should structure the document properly for future similar ideas.

- It’s just a thought, maybe Evernote will be better. How should I name the note? Am I ever going to look for this note again in the future?

- Meh, it’s not a big deal anyway. I’ll write it down if it comes back to me again. Then, it will be meaningful.

Does it sound familiar? That’s pretty much the decision process I was going through every time I wanted to take notes, and I’m pretty sure that thousands of ideas never survived that process – thousands of small ideas and thoughts that could have evolved into bigger ideas, now gone forever. Friction kills ideas, a little bit like the Earth’s atmosphere disintegrates small celestial bodies trying to make their way into the stratosphere. Alright, maybe not the best analogy.

What’s unique about Roam?

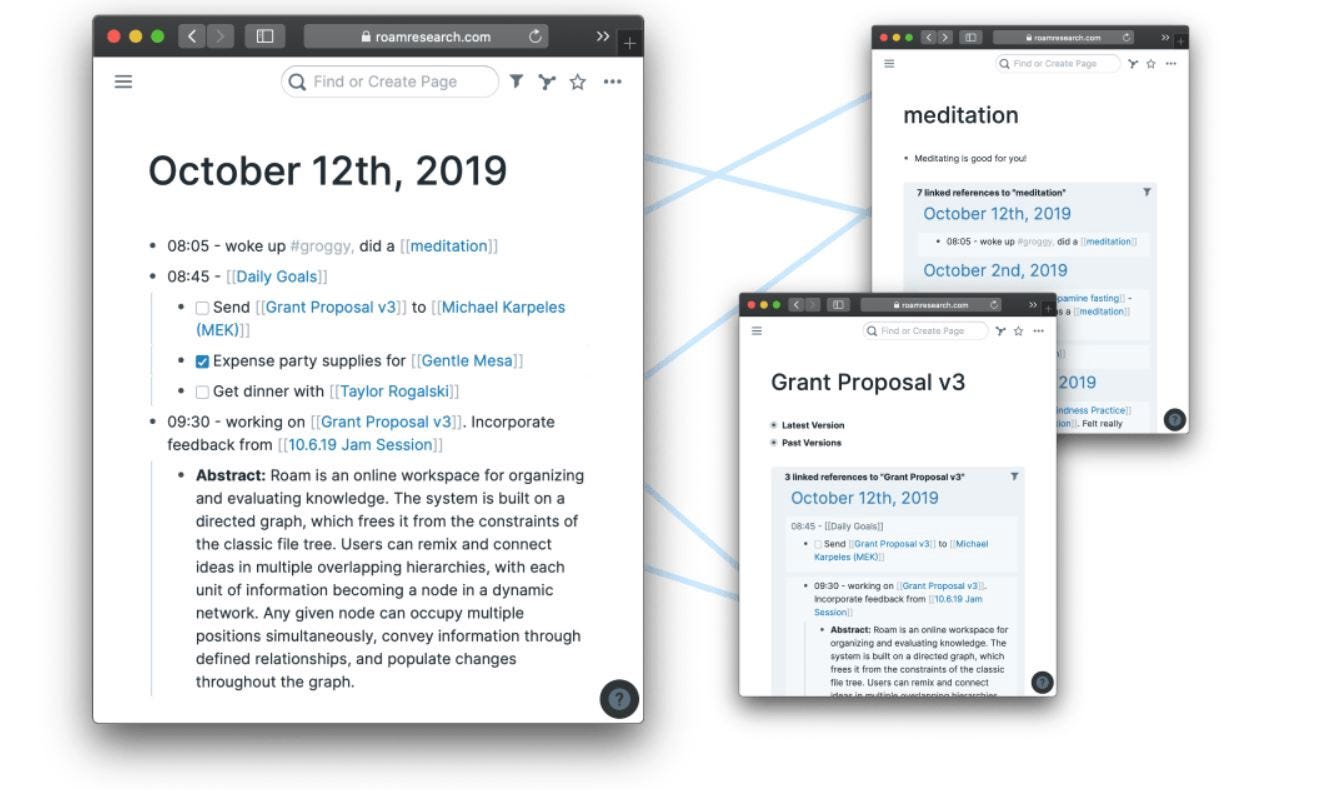

First, Roam allows you to take notes without asking you any questions. It automatically creates a page every day with today’s date as the title. Of course, you can create as many pages as you want, but you don’t have to if you only want to write stuff down quickly.

Second, it may sound counter-intuitive, but Roam removes friction by removing editing options. The whole page is a bullet-list that supports indentation. You can write something, indent with the tab key, and write more stuff related to that first idea. Stylistically speaking, you can set a block as a heading, use bold, italic, underscore, and highlight. And that’s pretty much it – no decisions to make about the look of the page.

You can create pages afterward by simply selecting text and encapsulating it with two pairs of brackets like [[ cool new idea ]]. It will transform the selection into a hyperlink. Clicking the link will open the newly created page.

This one may sound a little nerdy, but Roam offers bi-directional linking. Remember the link created above? If you click on that link, you’ll see a reference to where you created the link at the bottom of the page. Roam will keep track of all the pages that reference the link. It also works the same with tags.

Any bullet point is considered a unique block, and it can be referenced from anywhere within Roam. That means you can connect ideas on a block level, and when looking at link references, it will show you from which block it was referenced, not only the page.

Alright, it’s starting to look like an app review, so I’ll stop right there!

How it changed me?

By reducing friction to near zero (I always have Roam opened somewhere on all my devices), I have increased by tenfold the number of notes I’m taking daily. The only friction left is the effort required to type the idea on my keyboard, which is pretty low because I type all day.

I don’t have to worry about the “worthiness” or quality of my thoughts because I know that selection will occur naturally, as the most important ideas will be referenced more often.

Being able to look back at the paper-trail of my life logs has been incredibly helpful for self-reflection. I’m also less anxious about forgetting things that are meaningful to me.

And last but not least, I’m discovering new connections between ideas that I didn’t know existed. Adding more content is always exciting because I feel the potential for more emergence of ideas and connections. This is my long-term reward.

What I’ve learned

- Our ideas are born frail and fragile, and we never really learn how to nurture them.

- It starts with writing them down, which is a skill, and as with any skill, we get better with practice.

- Being aware of the friction created by our environment and making a conscious effort to reduce it will increase our chances of successfully building a habit of note-taking, and it will pay off in the long run.

References

- Roam Research: https://roamresearch.com

- “How I organize my life with Roam,” Ali Abdaal: https://youtu.be/bpikCLhpIRY

- Atomic Habit, James Clear: https://jamesclear.com/atomic-habits